Code of Conduct: An Integral Part of a Family Business Toolkit

Building Collaboration and Competencies in the Rising Generation

The dynamics understandably change once a parent, uncle, or aunt is no longer active in the business. When there are several members of the rising generation working together in the business, the successor leaders need to create systems and processes to make decisions, resolve conflicts, guide employees, and move the business forward. Even if only one holds the “title”, the team needs to create a collaborative environment with clear roles and responsibilities to lay the groundwork for success of the team itself and the business.

In this column, I will be discussing the Stewarts and Genro Co, a fictional family business where a sibling/cousin team has assumed day-to-day management and leadership from the founders, siblings Carl and Samantha. Samantha and Carl will ultimately pass along ownership to their children but before they do so they are looking for reassurance that the rising generation will have a productive, collaborative working relationship. In addition to the successors having the skills and tools to be a well-functioning team, the founders want the rising generation to understand and respect that their roles as managers and leaders, owners, and family members are distinct and, as such, have distinct functions and responsibilities.

When I first met with the Stewart sibling/cousin team, they were eager for strategies to leverage their strengths to achieve positive outcomes for the business and their family, and to develop more professional relationships at work. They are a close-knit group who wanted their interactions at work to be more positive, collaborative, and productive. They were looking to build their toolkit and develop a Code of Conduct that they could tap into when needed to help guide and support their interactions.

Although a Code of Conduct is often thought of as a statement outlining preferred and accepted behaviors, it can also be viewed more broadly as a collection of documents, policies, and processes that a family develops to guide and support their behavior and interactions and hold them accountable to each other and the family business.

The elements in a family’s Code of Conduct will vary just as each family develops policies and documents specific to their situations and needs. The Code of Conduct can be “institutionalized” by collecting the documents together in paper or electronic format, or by simply agreeing that the various elements are all part of the broader concept.

Ground Rules; Decision-Making; Information and Knowledge Sharing; Communication; Roles and Responsibilities in the Business; Roles and Responsibilities of Owners; Buy Sell Agreements; Conflict Resolution; Accountability; and Shared Values can all be considered parts of a Code of Conduct. Admittedly, these are not novel concepts to family businesses and those who work with them. Many of these elements are often developed into documents and policies to serve various objectives in a family business. (See Chapter 9, “Establishing Policies, Procedures, and Plans” in The Keys to Family Business Success). These policies, agreements and documents can also serve double duty and become part of a family’s Code of Conduct. In this column I will share how the Stewart Family approached several of these components and created their own Code of Conduct.

Establishing Ground Rules

One of the first steps in working with clients is establishing Ground Rules for meetings. The Stewarts were interested in communicating more productively so we took it a step further and developed a list of mutually agreed upon behaviors for all of their business interactions, not just our meetings together. As we worked on the list, they asked me, “what if someone is not following the guidelines or, despite our best attempts, something goes off the rails?” I encourage my clients to develop solutions together, rather than having me provide them, and this case was no different. The group decided they would create a signal that anyone could use if things got heated or seemingly intractable. The agreed-upon signal was the name of the family pet when they were growing up. They chose this as their signal because it conjured up warm thoughts and positive memories and could hopefully shift a challenging situation to a more positive one. In any case, the signal would indicate to everyone they needed to pause and regroup before continuing the conversation.

They came back to me at the next meeting and shared that one of them used the signal, but then they were stuck — they didn’t know what the next steps were. In this subsequent meeting we established: the person asking for the pause should share their rationale (briefly); which party would be responsible to reach out and make an overture; the importance of committing to reconnect; how to set themselves up for success when they do continue the conversation. This process shifts the focus away from the others and onto oneself, resulting in the opportunity for self-reflection and examining how each of them can play a role in both the challenging situation and its resolution.

Who Makes Decisions?

As a successor leadership or management team learns to work together, they often need to figure out who makes which decisions. Additionally, this new team may want to establish a different organizational structure, especially if decision-making had been more concentrated with the prior leader(s). In the Stewarts’ case, they were creating a flatter organization and so for them it was very important to understand and agree how they would collaborate on decisions.

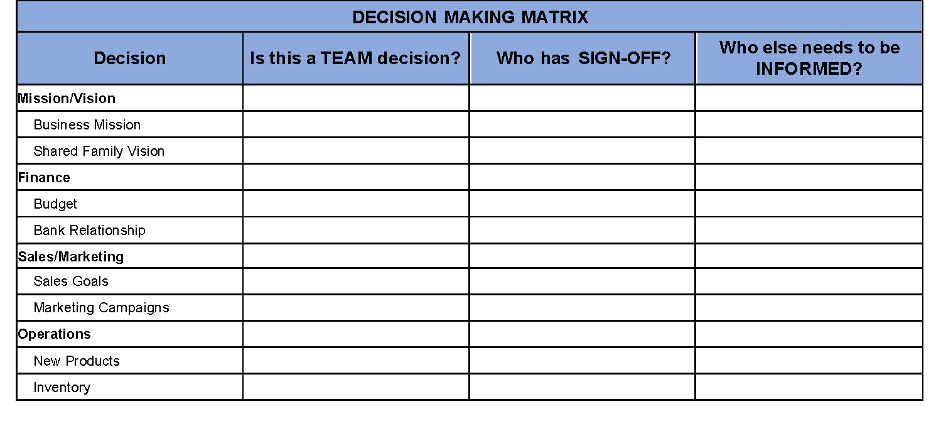

How many times have we heard: “How come you get to make that decision?” “Why wasn’t I told?” “Judith knew before me.” This is where the Decision-Making Matrix comes into play. This tool provides clarity about who might have the ultimate say, which decisions are collaborative among two or more individuals; who needs to be brought into the conversation and when, even if they are not part of the decision; and who needs to be informed. Communication is an integral piece of this too.

In the matrix (see figure below) the left-hand column represents departments and initiatives within an organization. These can range from large (strategy or budget decisions) to small (ordering office supplies or writing copy for an ad), depending on the structure of the team and the organization; sub-categories can be added as necessary or additional matrixes can be developed per department.

The headers of the columns define the level of autonomy or collaboration required for each decision, for example: is this a joint decision? Does one person have sole authority? Who else needs to be informed (before or after the fact)? Individual names are then filled in in appropriate places in the grid. In the case of a team decision, the team members’ names, or the team’s name, will go in the grid.

The Stewarts were aiming for a team approach. They wanted to collaborate as much as possible, but also agreed that certain circumstances require a final arbiter. They also wanted it clear to everyone who needed to be involved in which conversations. They named their column headings to reflect this. Businesses can adjust their headings to meet their individual needs and goals. In Genro’s case, team member names beyond the owning family are also entered into the grid in the appropriate fields.

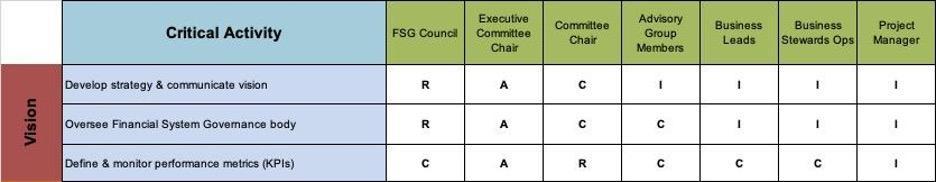

The RACI model is another useful framework. This can be used to outline roles and responsibilities throughout the company and for specific projects. This framework outlines who is Responsible (R) for doing the work; who is Accountable (A) to ensure objectives are met and tasks are completed; who is Consulted (C) and needs to provide input prior to completion; and who will be updated and Informed (I) on progress and decisions. Here the information is entered differently than in the matrix above: the column headings are names or teams, and the roles are entered into the grid. As in the example below, this framework is useful when there are many people and more than one team involved. RACI software and framework examples are readily available.

Both frameworks can help a family delineate and articulate which topics are business decisions, ownership issues, or family matters.

Roles and Responsibilities within the company can be another gray area when a new generation assumes leadership. Prior to the transition it is helpful for the senior leader(s) to delineate their responsibilities. This can add clarity to who among the next generation will handle specific work streams. At the same time, I encourage the new leader(s) to catalog their responsibilities and write job descriptions to get a clear picture of their areas of oversight and where they may overlap with each other. This can also highlight for them the distinction between items that fall under management or leadership purview versus the areas that are ownership or family topics. Being able to identify and articulate one’s job functions, in addition to understanding the different hats required for different situations, helps diminish role overlap and confusion, and also contributes to better Communication. This exercise helped the Stewart sibling-cousin team realize how to better separate their specific job functions from their roles as owners.

In addition to figuring out the new org chart, the Stewarts realized Genro needed a system to manage information so they could keep each other informed and be able to easily locate information. Some members of the team felt they didn’t receive information in a timely manner or have access to certain information. They developed a simple centralized location to store their documents, so everyone knew where to go. They also instituted a regular meeting schedule to provide time and space to discuss both ownership and high-level leadership topics, removing those discussions from management discussions. This, in concert with the decision-making matrix, ensures everyone stays informed and also has easy access to information.

The Stewart cousins also wanted tools to help them resolve conflict if they got to the point where none of the other tools were serving them. In Conflict Resolution, it is important to first determine the reason for the conflict. Are we disagreeing about the topic, do we want different outcomes? (Task conflict). Are we in conflict because we are at odds with each other, and we just do not get along? (Relationship conflict). Or do we disagree on how we are approaching the project at hand? (Process Conflict). Once everyone has a clear understanding of where the conflict lies, the involved parties can address the problem more effectively. The approach will depend on which type of conflict they are dealing with. In all cases, self-reflection and acknowledgement of one’s own role and goals are important in coming to a resolution.

The Stewarts have positive familial relationships and so did not want negative interactions that occur in the context of the business to carry over into their personal relationships. This provided them with the motivation to not only resolve conflicts but also examine how they each may have contributed to a conflict. During our work together the cousins explored their own behavior and tried to understand what part they played in the conflicts that arose. They also worked on adjusting their perceptions and behaviors to obviate future conflicts.

Forward Progress with a Code of Conduct

When a team is faced with figuring out how to work together, while at the same time establishing new systems and processes, it can be hard for them to arrive at straightforward solutions. The challenges can loom so large that it can be hard to see potential solutions. Whether a family does this work on its own or gets support from a third party, the Code of Conduct will reflect how they want to behave and treat each other.

The Stewart family now feels more secure in their interactions and business processes, and they know what tools are available to them to address challenges. The process of creating these various elements provided the opportunity for family members to explore their own behaviors and how they want to operate as a family in business together. The Code of Conduct ultimately provides accountability to everyone as individuals and as a group as they establish themselves as the new generation of owners and leaders.

Author(s)

SHELLEY TAYLOR

Shelley Taylor is a Family Business Advisor who works with business-owning families on matters pertaining to governance, structure, role clarity, next generation development, generational transitions, and family councils. ( view bio )